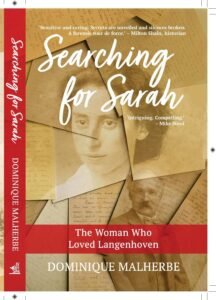

Searching for Sarah

Lawyer, writer, blogger. Dominique Malherbe is a name to be reckoned with. I’ve known her for a number of years and watched her reputation grow. And now comes her biography/memoir, Searching for Sarah (from Tafelberg). It’s her third book, following two memoirs – From Courtrooms to Cupcakes and Somewhere in Between. But memoirs are one thing, biographies quite another: so, Dominique, did this change in genre present challenges?

Yes, it did present many challenges. The biggest? Wondering if I had any right to tell the story and whether there may be something which I had completely over-looked which would leave a gaping hole. Also, all my source material was in Afrikaans which is not my home language and all the original Afrikaans passages had to be properly translated for me to write the English version. The addition and accuracy of footnotes added another dimension.

Then with both the Afrikaans and English versions, all original texts had to be checked and re-checked, not only to determine how accurate my original translations were but also to ensure that the spelling of the old Afrikaans words was correct as these differed quite substantially from current spelling.

Being in the middle of the pandemic also meant that the library was out of bounds and though 99% of the research had been done, there were still many references to be checked. Then there were all the photographs I didn’t know even existed. Needless to say, there were tons. And without the help and dedication of the librarian, it could never have been done by the deadline I was given.

The story of your great aunt Sarah and her relationship with the Afrikaans writer CJ Langenhoven had long been a part of your family’s stories. What was the essence of the family stories?

The family stories were in fact very few and quite insubstantial. It wasn’t as though we sat around the dinner table discussing her much. All I recall is a general impression that Langenhoven was only ‘something’ because of Sarah. And that Sarah was entirely devoted to him. There was also the whisperings of a child.

What made you decide that it was worthwhile investigating further?

I’m not sure it was a decision I consciously weighed up. I simply started travelling to Stellenbosch library to see if I could find something of her in there once I knew that a masters’ thesis had been written about her. And because I knew Langenhoven was something of an intriguing character himself.

So you’re sitting in the Stellenbosch university library reading about your great aunt and you’ve ploughed through the Kannemeyer biography of Langenhoven, but what made you decide that you should write her story?

I suppose I felt a sense of ‘well, this story should be revealed.’ There was such a comprehensive catalogue of their letters and general correspondence with so much history and so neatly and thoroughly kept that I felt it was almost just sitting there waiting to be discovered. And then the issue about women in general I’ve always felt strongly about too: the age-old patriarchal superiority story and the invisibility of women in history in general that intrigued me. It seemed such a fascinating story.

Did you find people willing to talk about Sarah and what they knew of her life?

There weren’t many, in fact, who were still alive that knew her. I started with whom I discovered were her truest friends – so Elsa Joubert, Audrey Blignaut and ME Rothman – and only Elsa was still alive. But other than that, many people had an opinion about her. Or thought they knew something which intrigued me.

Interviewing people is always tricky. What did you find was the best way to get your questions asked and answered?

To be as informal and friendly as possible. To make them understand that I really knew nothing (which was entirely true) and that I would be grateful for anything they knew.

As the material from personal accounts accumulated, how long was it before you decided to dig around in the archives?

Once I realised that the material in the Stellenbosch library had originally come from the national archives, I felt that I had to go there to ensure that nothing was left there. I also knew that all estate details – records of death at least – would be found there.

You clearly enjoyed the archival and library research. At what point did you decide that this was not only a biography but a memoir about trawling through the documents in search of Sarah? Or did it just come about naturally as part of the writing?

I didn’t really consider what genre of story I was writing. I wrote it as I experienced it and since that has been my style of writing (ie memoir), I didn’t really know any other.

Clearly you met with some guarded reactions from some of the people you spoke to. It seems extraordinary that a relationship that existed a century ago and two people who have been long dead should still make people uneasy.

Yes! This was a really fascinating part for me. It felt as though there was some big mystery behind it all and no one wanted to enlighten me.

As you dug ever deeper into Sarah’s life, I know there were unexpected revelations. For instance, you uncovered references to a possible rape and evidence about a child. Had you known about these in advance?

I knew nothing about a rape at all. All I had heard was that Langenhoven and Sarah had had a child but no one could tell me when or where or what had happened to him.

Langenhoven has a huge reputation and was lionised by his biographer Kannemeyer. In a sense you were constantly up against this image of Sarah that Kannemeyer had created – an unflattering image of a woman building her own image on that of this doyen of Afrikaans literature after his death. Do you think you have managed to set to rights the prejudices?

This was perhaps the most daunting part of this book. I am not even half a biographer. Kannemeyer is renowned as a great biographer. Of many, many works. But as I researched the story I became more confident that this story was not about Langenhoven but rather about Sarah and I had to remind myself that he couldn’t have known all of her side – especially the family part. I truly hope I have gone some way in putting forward her story from another perspective. But I don’t believe that prejudices disappear quite so easily – by simply telling a story. Prejudice seems to me like an inbuilt, perhaps even genetically transferred human trait that will take decades to undo.

Were there ever any moments when you thought the book might get the better of you, that it might be too sensitive a topic even today?

I’m not too afraid of sensitive topics. I generally speak my mind and have an opinion and love to discuss and explore issues in the world. The thing that bothered me is that I felt I was an ‘outsider’ in this story. That serious Afrikaans literary folk knew far more about Langenhoven in general.

Your title is Searching for Sarah. Do you think you found her? Or were there still elements of her life that will remain forever hidden?

I have definitely found part of her, possibly quite a substantial part though there are still many gaps. I’m hoping though that more will come to light once the story gets out and people start to talk and question and this might provide further links to possible family.

Let’s move to the writing: how long did it take to write the first draft?

Oh gosh. That’s a hard one. A first completed draft? It took a few months of scattered writing to get something together to send to publisher. I think I only had between 30,000 – 40,000 words at this stage and a rough skeleton outline of the chapters. I only finished a complete first draft once I secured a publisher as I felt as though I couldn’t do it alone – especially with all the Afrikaans. So I finished my first draft in about three months after that. I wrote from April to end June 2020 and was it sitting at about 80,000 words at that stage.

At what point did you get a publisher? And how did this come about?

It was a weird, exciting, frustrating and breath-holding process. Early on, when I had about three chapters, I had some discussions with a publisher regarding the kernel of the story. They were encouraging but adamant that the story be written in Afrikaans – which I was certainly not skilled enough to even consider. A few months later (around February/ March 2019) I was then in discussions with another publisher (still not having written more than about three chapters) and they too were keen and excited but wanted something different as an ending and I couldn’t deliver on that promise. Shortly thereafter, my current publisher expressed an interest, but I needed to almost complete the manuscript before they could consider it. I submitted my first proper draft in November 2019, I think, and was finally given the go-head in April 2020.

Searching for Sarah is to be published this month (April 2021). Have you moved onto another writing project? If you are would that be more non-fiction or are you branching out?

I have some new ideas for three very different writing projects. I am working on my first piece of fiction (in the Masterclass – woohoo!!) and really hope to do something with some 50,000 words I wrote during the month of November 2019. I used some of this as a start of a work of fiction on the Masterclass last year but then Sarah took over and I couldn’t manage both. I’d also like to go back to a more serious work of legal professional ethics that I started a few years ago which was commissioned by Juta. I feel strongly about the state (and perception) of the legal profession in this country and feel that there is much work to do in this field. It’s the strength of the justice system in general which I believe impacts on the health of a country as a whole.

But I also feel the need to complete the third in my series of memoirs as there are some lose threads there. And in a period of an interminable pandemic and aging parents, I see an urgency in this. It would be a sort of love letter to my parents.