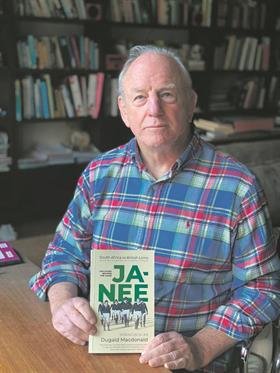

Windgat – an interview with Dugald Macdonald

In a wonderfully frank interview that’s not at all windgat, Dugald talks about getting the idea for his book, researching it, writing it, and watching it become a bestseller. Most importantly, he’s got interesting things to say about the writing process.

So Dugald, after being turned down by five publishers you have gone on to successfully self-publish a remarkable memoir – Ja-Nee – The Story Beyond the Game – that is a top seller in a number of bookshops. It’s about a rugby game you played in as a Springbok against the Lions more than forty years ago, but it is so much more than yet another rugby book. You’ve produced social commentary, you’ve rewritten history and, most importantly, you’ve written an account which is highly readable and very funny.

According to the prologue, the story came to you as you browsed old copies of Huisgenoot and Scope in a Kalk Bay bookshop, a seemingly random bit of browsing. It makes for a great opening, but was this really its beginning or had you been stewing on the story for years?

Stewing! That’s a good word. I stewed over that game for a long time. The wrong kind of stewing. Morbid, stuck and unproductive. How was it possible to play that badly? The worst defeat in South African rugby history? On and so on… Surprise, surprise. Other Springbok teams play just as badly. You are not alone.

But the tough one to deal with is the reality that I wasn’t picked again for South Africa. A one-test wonder. My idea of the hero’s journey didn’t cover that. Unrequited love for a Springbok…

But failure and disappointments have the power to drive you in other areas of your life like nothing else can. This is not a rugby thing. It’s a human thing. You’ll never forget the moment your boss put you on notice. Or when you were fired. Or not hired. The slights. They never leave you. Hang on to them. They’ll come in handy when the publishers turn you down.

If I’d played in another test I would never have written the book. Whatever power the book has comes from that reality.

What makes a sportsman’s experience vivid is that you dream and visualise it all from your early years and then the next day you’re 32 and its all over. If an injury hasn’t ended it earlier. Or the opposition. All of it with the world watching. You can aspire as obsessively to be a doctor, to act, to be an engineer, but the sportsman’s allotted time to do his carpe-ing is short with a large opponent trying his best to make it shorter. I’m 72 now and I’m only starting to write. Who knows, maybe the best is still to come. Everybody has failures. Hang on to them. They’re powerful friends.

So much for the existential stuff.

I’d written some pieces over the years under your supervision, but I’d never got stuck into a book-length project. I had dwelt (as opposed to stewed) over writing something about rowing across the Atlantic Ocean or walking to the North Pole but I never seriously considered rugby as I hadn’t really had a career of test matches, which is the stuff of rugby books. All I had was one game 45 years ago which we lost handsomely so to speak.

At this point I came across the Huisgenoot issue 2730 with the 16-page supplement about the 1974 British Lions tour. The articles included extracts of radio commentator, Gerhard Viviers, commentary of the match. In the one about the second test he starts “…this is without doubt the most important match in South African history”. This was like a physical blow. “Really? Did I play in the most important game in SA history? I ordered the recordings from the SABC, transcribed them and with the Huisgenoots was completely drawn in.

Of course, my morose whinging voice dismissed the thought of writing about it out of hand. But then I discussed it with you and without your encouragement the whinger would have prevailed. So there was stewing and dwelling and incubating. The magazine was the trigger. There was also the spectre of my 70th year hanging over the whole idea which gave it a sense of desperate intensity. Now or never. Carpe bloody diem et noctum, bru! Forty-five years later, it’s August 2021, and I’m on the cover of the fucking Huisgenoot!

Hang on to those slights.

- When you started writing did you know where the story was going or did that happen along the way?

My Springbok CV is not the material of a great sports book but I started to see that told in a certain way it could be unique. There are many sports books that deal with one game. None are written by a player playing his only game for his country – a game that is lost by a record margin. None use the structure of the game itself and the commentary of someone who is commentating on that game in real time. He’s actually describing what he’s seeing in real time. He’s not recalling or reporting second hand.

It was basically the structure of the Huisgenoot issue 2730, blown up into a book. So then I took the transcript, listened to the recording and started to pick out bits that stood out for me and started to comment on them. React to them.

Obviously, there were incidents in the match and around the match that I knew would arise but most of the time I was listening to descriptions of stuff that I had no recollection or knowledge of in the first place. At the beginning I knew that certain stuff I would have to talk about, but 70% of the content suggested itself along the way. I really had no idea of how it would end up.

Once I got going it was a question of making choices, there was a lot of stuff I could have added. It was a case of what to leave out. The Huisgenoots were amazing material. I could have written a book about that one issue. Come to think of it that’s not a bad idea.

I knew that I would have to place the story in a socio-political context but I had no idea where these pieces would come from. They just suggested themselves along the way.

Listening to an awed Gerhard Viviers describing the struck-dumb, dead-still spectators prompted the thought that these folk were someone’s constituents. The East Stand at Loftus Versfeld controlled the pace of change in South Africa.

Fans didn’t go to Loftus with their copies of Frantz Fanon. They went with naartjies by the sack to pelt the visiting team. I was conscious of keeping the socio-political stuff subtle and nuanced. The ‘a’ word [apartheid] only appears once. It’s one of the words on a banner unfurled by demonstrators. Even then I was reluctant to use it. I think the reality of our time lurks behind the story. I think it is more striking for that.

- Did you ever doubt what you were doing? Did you wonder if you could pull it off?

Doubt? All the time. I have never sat and written anything longer than 2000 words. Probably too short for the critical voice to break me. But 90k words is another story. There were many moments when I came close to canning it. Most sportsmen have a coach or mentor or important figure in their careers who can encourage and affirm that they have what it takes. That person needs to be qualified to give career breaking, tear inducing advice.

That was the role you played. A professional to be taken seriously, confirming and reconfirming that my stuff had merit and that I should take it to the end. Along the way I met the critical voice that I’d been warned about. The one that says, it’s crap. Who cares? You’ve got better things to do. This is not a legitimate way to use your time. You’re living in the past. Get over it.

In a way that defeat is what drove me to finish writing about that defeat. The fear of failure is a potent force. With Nicol in the background winding me up even tighter…

- The research you did was critical to the story. It seems to have been a gradual unfolding of an alternative version of that game, is that how you experienced the process?

A gradual unfolding. If I’d written the book from memory some extraordinary stuff would have passed me by. A purely rugby example: I had no recollection that the Lions had used their hooker to throw in while South Africa had used their wings. It was only in listening to the commentary that I realised this and the influence it had on the game. So then the research started. Not exactly riveting to the general reader but fascinating to me regardless of whether it ended up in the book or not. Material suggested itself along the way which would then require research which in turn takes you to unintended destinations.

- Your style is distinctive, very funny, frequently subversive, and it is difficult to imagine this book being written in any other way. Was it a style you hit on fairly early in the writing?

I’d written plenty of short humorous pieces before for my own amusement but which I’d never let out of the room. For example, an obituary of Caravaggio’s mother: A lovely lady with a dodgy hygiene record.

I was fortunate to grow up in an era of mould-splitting comedy. Hancock, Milligan, Sellers, Woody Allen, Python all teetering on the shoulders of the Marx Brothers, Brooks, Lenny Bruce, Wodehouse, Waugh, on and on and on. They’ve all been washing about in this incubator for 50 years. You’ll find their fingerprints on every page.

I started on the assumption that I should write in conventional non-fiction sports journalist prose. That was the way sports books are written. But I kept going off-piste so often that I decided to stay there. A distinctive voice you called it and advised me strongly to let it have its way. I expected it to evaporate but it was still there at the end. Hopefully it will be around for a while.

The book was written in a style that has no place in a sports book. It stands out because of this.

- To return to the humour, it is an intrinsic part of your memoir, in fact, it makes your points all the more telling. Is this ironic distance a deliberate device?

You can get away with all sorts of stuff if you make it humorous. More than you can in normal prose even if you’re saying the identical thing. There’s nothing new about this but it was only as I wrote that I sensed the opportunities and how extraordinary this phenomenon was and the scope it allowed for serious piss-taking.

Consider the following statement: “If there had been majority rule in SA in 1974 the country would be a basket case today.” You’d be ill-advised to say that too loudly.

But there’s plenty of that in the book. I even talk about the civil war that would have broken out if there’d been majority rule in 1974. It can easily go to your head once you crack it a couple of times. All neatly camouflaged with subtle and not so subtle humour.

- You mention that none of the South African players have written about that game against the Lions in 1974, yet almost all the Lions players have. Your book reveals that apart from lucky breaks and some manufactured opportunism, the Lions had nothing to write home about. Did you expect this result when you set out to tell your side of the story?

‘Nothing to write home about’ is a bit strong but certainly it was amazing to see an alternative version of the game emerge once it was analysed in the finest detail. If nothing else it’s a classic bit of revisionist history that will be hard to argue with, unless you’re prepared to put the work in that I did!

The stats are there. The descriptions are there. I never discussed the book with my former teammates so all the analysis and, importantly, the conclusions are mine alone. I read the books, the press of the day, the video footage of the tries (there is no video of the whole game, just the tries).

The game was 48 years ago. The book was published almost a year ago. So since then further thoughts and reflections have surfaced. At the time I experienced it as a slaughter. The revisionist view is that it wasn’t that bad, there were many what ifs. For instance, all the bounces going their way, infringements not spotted by the referee, the low cunning and sleight of hand. I still called it a great cutting apart. But now a year after publication the feeling of a slaughter is back.

- As far the nitty-gritty of writing is concerned, do you work to a certain number of words a day, or do you write in spurts?

Discipline means following the rules especially when it doesn’t suit you. A practical way around this is to have no rules. I know it’s going to be impossible for me to follow them so why bother. An aversion to making rules for myself and committing to them is the problem. This is a major weakness. No rules. No structure. No deadlines. Just huffing and puffing procrastination and inertia. Reading about writing and re-editing the already edited are favourite pastimes.

Your rule of 250 words a day: Why can’t I say: “I will write 250 words a day. Everyday.” I look at that number now and ask how did it possibly take me that long to write that book? I still haven’t taken that vow. It’s taken me almost four months to answer your questions! That I’m not alone in this is some consolation .

So as not to write myself off completely there were some moments when I wrote creative, descriptive pieces that felt as if they might not have come in a tightly structured writing schedule. But I sense this is bullshit as well. I need to commit: 250 words a day. Everyday. What’s so difficult about that? I’ll start tomorrow. No, Monday. The start of a week. Come to think of it, it’s almost the end of the month. First of February?

- How long did it take to write?

I started on the Masterclass of March 2019. You finished the final edit in February 2021. It was on the shelves late May 2021. It should have been comfortably finished by mid-2020 at the very latest. There was quite a bit of reading and research to do and, given the nature of the book, it was never totally clear what would come next. Of course, getting stats from the commentary and a record of the backwards and forwards of the game, and analysis all took time. Counting the number of times my name was mentioned did not take long!

I hand wrote everything on one side of an A4 notebook and then sort of corrected it and improved it on the blank page opposite. Then I typed it. I spent a lot of time rereading, editing, changing and fiddling and admiring my brilliance. It seems that I’m not alone in this either. I like the feel of writing by hand, the sense of words flowing onto the page. The magic moments when you sit back and think: “Where did that come from?” It seems that even a novice can have these.

When I felt that I had more or less got a section right, I typed it. One hand, two fingers. Sometimes three. Max. Come to think of it, under the circumstances, I did it in a record time.

You’ve had remarkable success with your book and wonderful tributes, what have readers most appreciated?

The humour is the first thing that people refer to. It’s not the type of book, a sports book, that one associates with humour. In addition, mine is idiosyncratic so that comes as a surprise. Despite the tone of the book, a lot of it is serious rugby history and social commentary so to tell it in the way I did is unusual.

The Lions were here last year, 2021, and before the do or die second test their forwards coach quoted bits of Ja-Nee to his team. He said it was helpful to understand the South African rugby mentality and the psychological state of their opponents which they would be facing. It’s actually a good handbook for anyone wanting to understand our rugby mentality.

It has had a wide cross-section of readers. Not just people of my era and not just males and not just sports followers. I was pleased that critics described it as “Not another rugby book”. That they felt that the writing had merit was especially rewarding. “Compelling” and “compulsive” was how some readers described it. Some guys really got it. All of it. Every morsel there was to be had they got it. The memoir, the history, the social commentary, the players, the commentary, the language. They devoured it. They wailed and they hooted. They snorted. They read each other extracts. They saw stuff that I didn’t see. They rationed their reading. They really really got it. Every bloody word.

Windgat? Who me?

From A Dictionary of South African English: windgat – braggart, ‘blowhard’, conceited